The venture capitalist's dilemma

The embarrassing investor meltdown surrounding Silicon Valley Bank should drive us to consider new models.

A little less than a year ago I made some venture capitalists very angry when I made an offhand remark in an episode of Crypto Critics' Corner: "I mean, I would probably argue that venture capitalists are not good for society regardless of what they're investing in." I am always surprised at how controversial a statement that is, and how much it attracts the kind of "not all venture capitalists!" sort of reaction that's usually reserved for criticism of cops and landlords.

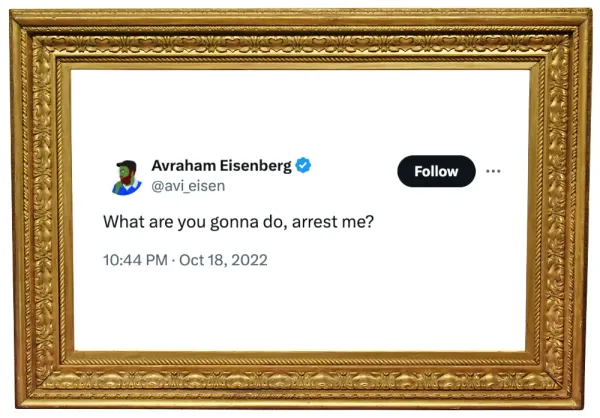

I am feeling particularly secure in my opinion on the investor class after the shitshow we just witnessed, where a relatively small group of venture capitalists and various other financiers did not, let's say, cover themselves in glory.

When it became apparent to this small group of very powerful, very wealthy individuals that Silicon Valley Bank — the bank used by much of the Silicon Valley startup ecosystem — was on shaky footing, they had a choice to make. They could remain calm, urge the founders of companies they'd invested in to do the same, and hope the bank could weather the storm. Or, they could all pull their money out, urge their founders to do so also, and hope that they or their companies were not the ones left standing in the teller line when the liquidity dried up.

Faced with the choice between the more communal, cooperative choice and the self-serving, every-man-for-himself choice destined to end in a bank run, it should be no surprise which option they picked. As the Titanic sank, they were the ones pushing people out of the lifeboats.

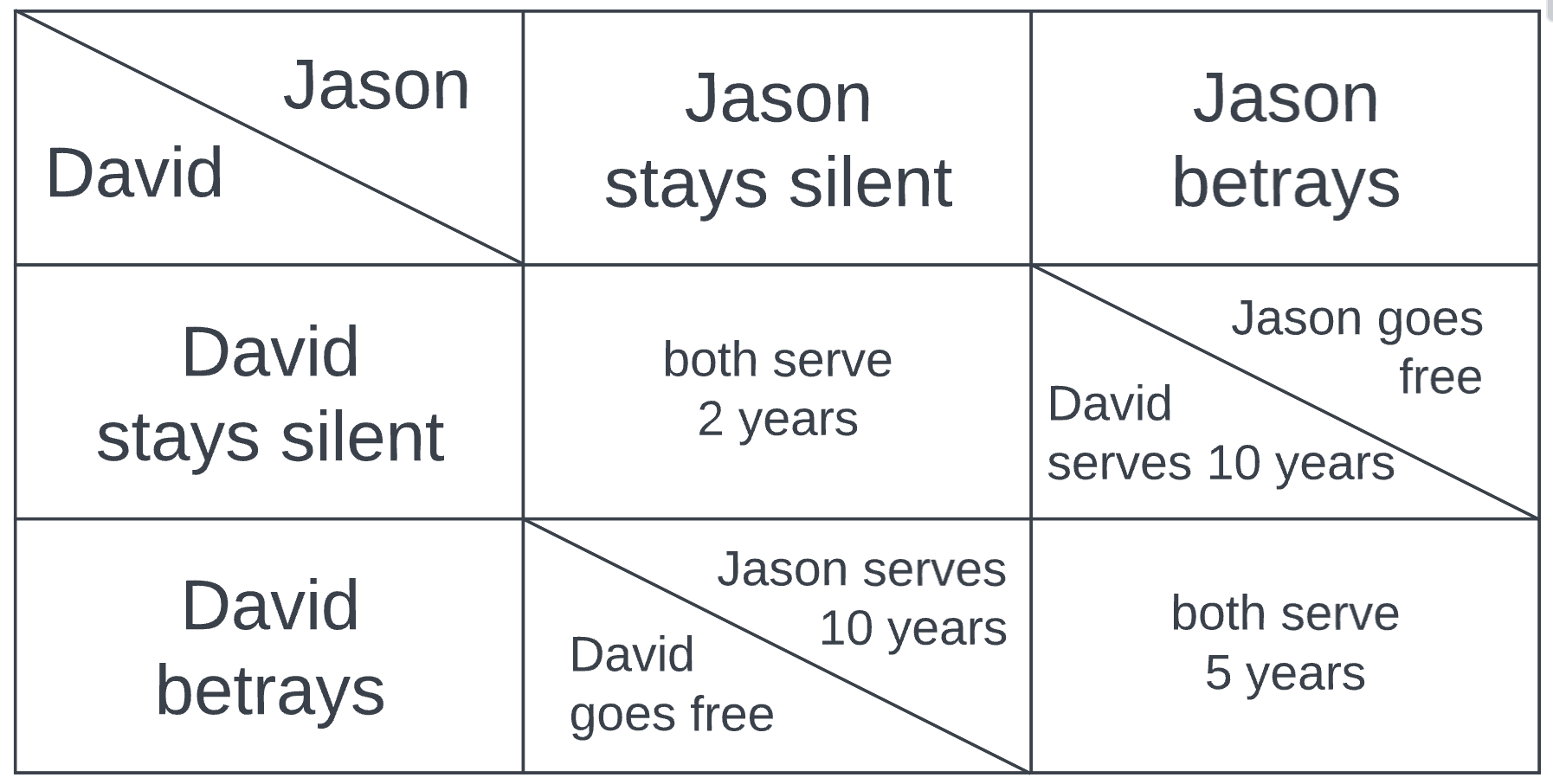

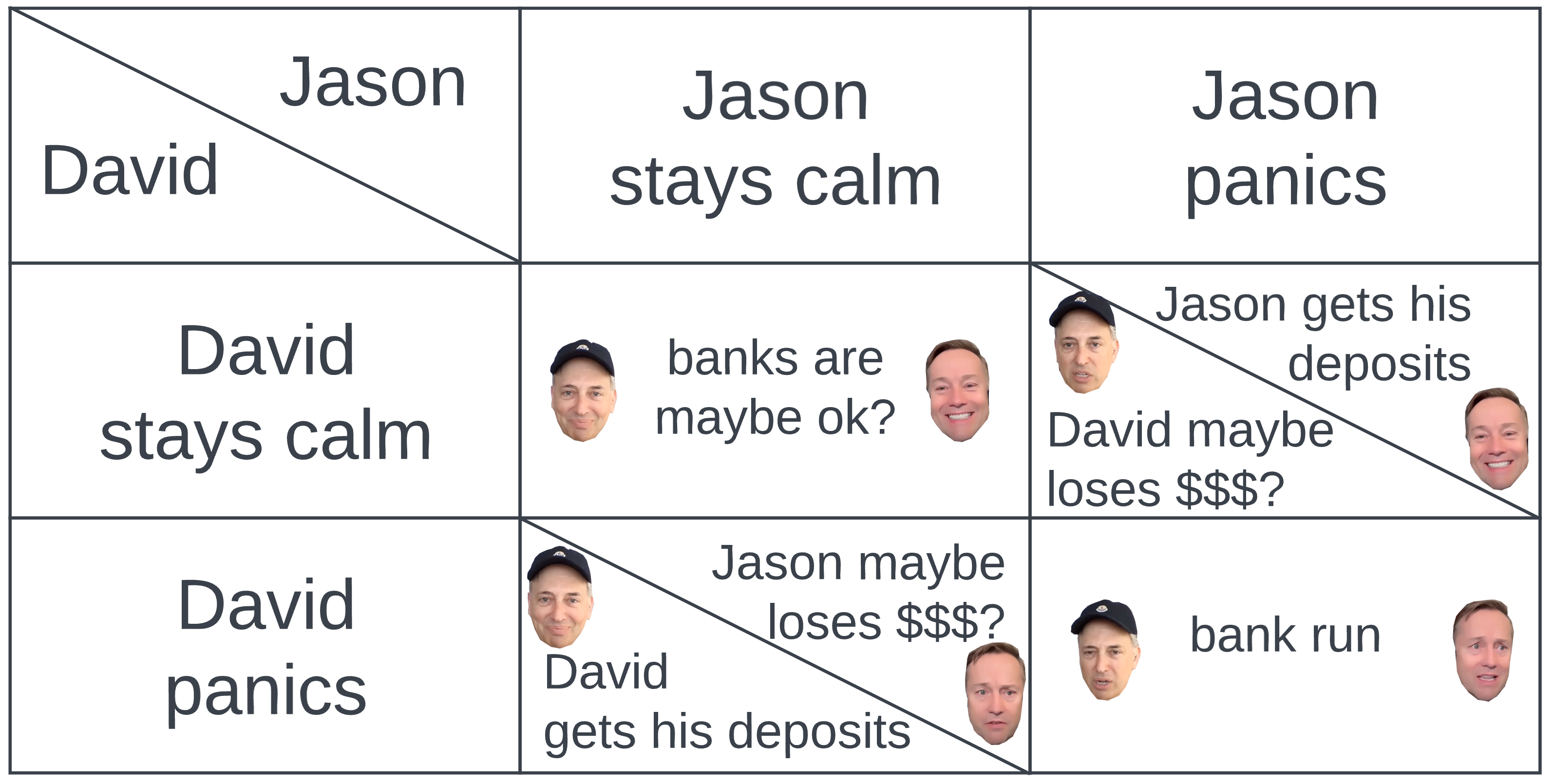

For those unfamiliar, the prisoner's dilemma in game theory refers to a scenario in which two prisoners arrested in connection to the same crime are each offered a bargain if they betray the other. Neither has any insight into which choice the other prisoner will make. The prisoners are usually referred to as "A" and "B" but to make things a little more personable, and for absolutely no other reason than that, we'll go with the names "David" and "Jason".

If David and Jason both remain silent, they will both serve a lighter sentence of two years, because the police don't have the evidence to convict either of them on the more serious charge. If David betrays Jason and Jason remains silent, then David goes free and Jason serves the entire, greater sentence of ten years. Same if the roles are reversed. If each betrays the other, they split the greater sentence and serve five years apiece. We can represent this all as a simple chart:

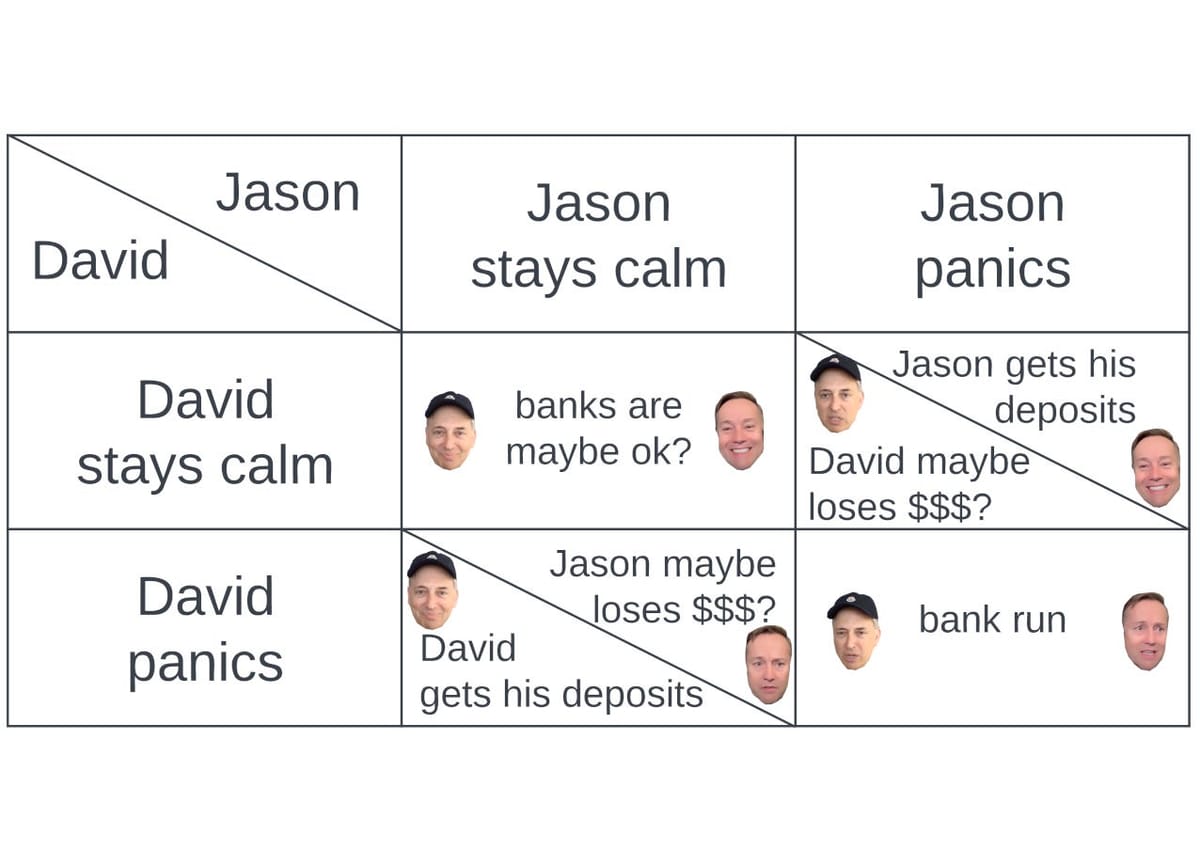

If we now extend the analogy to the Silicon Valley Bank bank run, we have a similar-looking chart, although critically the scenario in which both David and Jason panic is actually likely to be a worse scenario than the one in which one of them stays calm and the other panics.

However, this is a somewhat flawed analogy when we look at what actually happened. In reality, the investor class panicked, they received their proverbial "sentence" (the bank run), and then they walked up to the cell door and shouted at the guards "you can't do this to us! you'll ruin everything!" and the guards — long-time allies of the prisoners — said "you know what, they're right" and handed the keys right on over.

Anybody who thinks that preventing bank runs and panics isn’t a federal responsibility missed a couple hundred years of financial history. It’s called systemic risk, and only federal banking authorities can stop it.

— David Sacks (@DavidSacks) March 10, 2023

Venture capitalist David Sacks (archive)

YOU SHOULD BE ABSOLUTELY TERRIFIED RIGHT NOW — THAT IS THE PROPER REACTION TO A BANK RUN & CONTAGION @POTUS & @SecYellen MUST GET ON TV TOMORROW AND GUARANTEE ALL DEPOSITS UP TO $10M OR THIS WILL SPIRAL INTO CHAOS

— @jason (@Jason) March 12, 2023

Angel investor Jason Calacanis (archive)

Now, don't get me wrong, the Fed's not-a-bailout of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank seems ultimately to be the right choice in an objectively bad scenario. Depositors will be made whole, and companies are no longer facing fears that they won't be able to make payroll or keep the lights on. But the circumstances that led up to this disaster, and the people we allowed at the helm of the ship steering full-steam towards the iceberg, ought to be questioned.

We have found ourselves in a scenario where the investor class has, yet again, managed to privatize profits and socialize losses. While many of these powerful, wealthy, and connected individuals have pushed for policies that would scale back government and regulators, promoted cryptocurrencies they believe to be outside control of the state, and pushed back against any action to break up tech monopolies, they quickly found themselves begging government officials for a rescue. "No atheists in a foxhole. No libertarians in a bank run," tweeted Eric Newcomer, after right- and libertarian-leaning David Sacks tweeted at government officials demanding they "Stop this crisis NOW".

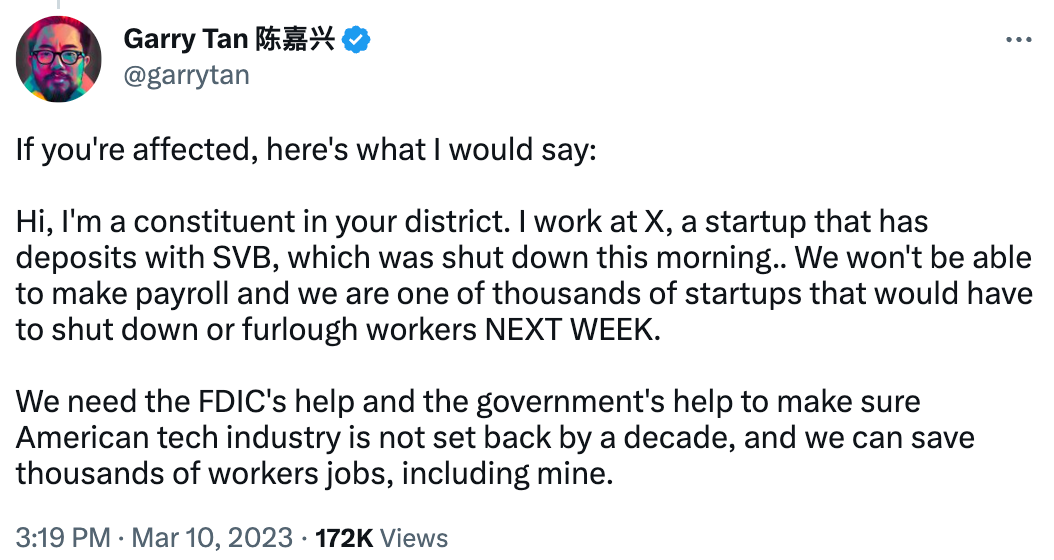

During the SVB crisis, the investors who took to Twitter to beg that people pressure officials for a government rescue seemed uncharacteristically self-aware that their popularity has waned in recent years. Although some attempted to sing the praises of venture capital, and warn of the supposed consequences of it being hamstrung by such a severe banking crisis, most seemed to realize that this might not widely land, and instead tried to shift the conversation towards concern for the relatable "little guy". They trotted out examples of small, mom-and-pop style businesses who banked with SVB and who might go under if their deposits became inaccessible. They pointed to biotech companies or life sciences companies who developed life-saving medications who banked with SVB. They warned of an "extinction level event for startups [that] will set startups and innovation back by 10 years or more",1 urging startup employees to send form letters to their representatives to say they feared for their jobs:

But this supposed concern for employees was difficult to swallow given the level of contempt for employees and "the little guy" that we have seen from the investor and executive class over the last several years. Those who once saw fit to demand workers risk their lives for the sake of their employers during a global pandemic, who rampantly union-bust, who ruthlessly slashed jobs when interest rates began to increase, and who alluded to ways they could circumvent severance payments now magically found within themselves a feeling of concern for the poor employees, those people just trying to put food on the table.

"On Monday, 100,000 Americans will be lined up at their regional bank demanding their money—most will not get it. This went from Silicon Valley investors on Thursday to the middle class on Saturday—Main Street finds out Monday", tweeted angel investor Jason Calacanis in all capitals. "Since when do Main Street Americans have >$250k in their checking account?", replied a follower, to which Calacanis replied, "The company they work for does". The multiple levels of absurdity in Calacanis's tweet were quickly pointed out in his replies, by people who questioned why an employee would be lined up to try to withdraw money directly from their employer's bank account, or why payroll would be coming out on a Monday.

But Calacanis's ridiculous tweet demonstrated what he and other members of the financier class realized: there was little sympathy to go around for him and his ilk, and so he needed to come up with something to mask the self-serving rescue they all desired as concern for the hoi polloi. This was concern that Calacanis miraculously managed to conjure up sometime after his April 2022 text messages2 to Elon Musk, in which he suggested slashing headcount in a way that would not require Musk to pay severance:

Day zero

Sharpen your blades boys 🔪

2 day a week Office requirement = 20% voluntary departures.

When the financiers' pleas weren't well received, and particularly after the rescue had happened and they no longer needed to focus as much on their image, some of them took to various platforms to express horror at what they claimed was disdain for small business owners, the tech industry, or white collar workers.

"I believe that if Silicon Valley Bank were instead called Farmers Bank Of Santa Clara (they bank a lot of winegrowers!) we would have had this easily resolved. unfortunately it became somewhat political," tweeted entrepreneur, investor, and eyeball-scanner extraordinaire Sam Altman.

"The search for scapegoats, I think, is getting out of control, and it's just not factually accurate," said venture capitalist David Sacks on an episode of the All In podcast, which he co-hosts with three other Silicon Valley investors. "And it's convenient to make tech, which his hated right now… the scapegoat," agreed co-host Calacanis. Later in the episode, Sacks echoed the opinion that "so many people" hate tech as an industry, and claimed that these same people believe that "consumers and small businesses" should suffer.

But it was not the tech industry as a whole, its employees, or consumers and small businesses who were on the receiving end of the broad disdain that we saw throughout the SVB collapse. It was the financiers.

We are coming to a point, I think, where the shine is wearing off. People are realizing that despite the hundreds of billions of dollars being deployed each year by venture capital firms in pursuit of "innovation", the world doesn't really feel hundreds of billions of dollars better off for it. For all the talk of unbridled innovation, venture capital services only very specific types of innovation: those that stand to produce large exits for investors, and with relatively low risk, regardless of whether the business itself holds much promise or provides any societal benefit. As Edward Ongweso Jr. writes for Slate:

For the past 10 years venture capitalists have had near-perfect laboratory conditions to create a lot of money and make the world a much better place. And yet, some of their proudest accomplishments that have attracted some of the most eye-watering sums have been: 1) chasing the dream of zeroing out labor costs while monopolizing a sector to charge the highest price possible (A.I. and the gig economy); 2) creating infrastructure for speculating on digital assets that will be used to commodify more and more of our daily lives (cryptocurrency and the metaverse); and 3) militarizing public space, or helping bolster police and military operations.

We are overdue as a society for seriously questioning what has become, but what has not always been, the dominant model of "innovation". Recent weeks have drawn a bold underline beneath what has been clear to many for a long time: that those controlling massive amounts of capital and power in our society are not the smartest, or most level-headed, or most altruistic among us. Venture capital may be the best way to serve the interests of capital, but we need to consider alternative models that prioritize the interests of people.

Further reading:

- "The Incredible Tantrum Venture Capitalists Threw Over Silicon Valley Bank", Edward Ongweso Jr. at Slate.

- "Euthanasia of Silicon Valley Bank", This Machine Kills. (Podcast).

- "Big Banks Trust First Republic With Their Money", Matt Levine in Money Stuff at Bloomberg.